The Case for Whole Novels: How and Why You Should Teach a Full Novel in a World of Excerpts

In classrooms across the country, full novel studies are quietly disappearing. Curriculum guides are slimming down, pacing calendars are tightening, and more districts are replacing whole books with short excerpts. The justification is always the same: “You can teach the same standard with a passage as you can with a novel.”

Technically, that’s true — but it’s also deeply misleading, and the cost is enormous. Students are losing the opportunity to build the very skills colleges say they’re lacking: stamina, deep comprehension, and the ability to follow complex ideas across time.

Here’s the truth: Whole novels aren’t the problem. How we teach them is.

A standards-based novel study isn’t about reading every page together or filling time with projects. It’s about intentionally designing an experience that builds stamina, deepens comprehension, and connects reading to meaningful writing and discussion. When done well, a novel study becomes the most rigorous, joyful, and transformative part of the year.

So if you’re wondering whether you’re getting the most out of your novel study — or if you’re trying to defend whole novels in a world obsessed with excerpts — this blog post is for you.

Here’s how to teach a novel so it’s worth teaching the whole thing.

1) Begin and End with Purpose: Set the Stage and Stick the Landing

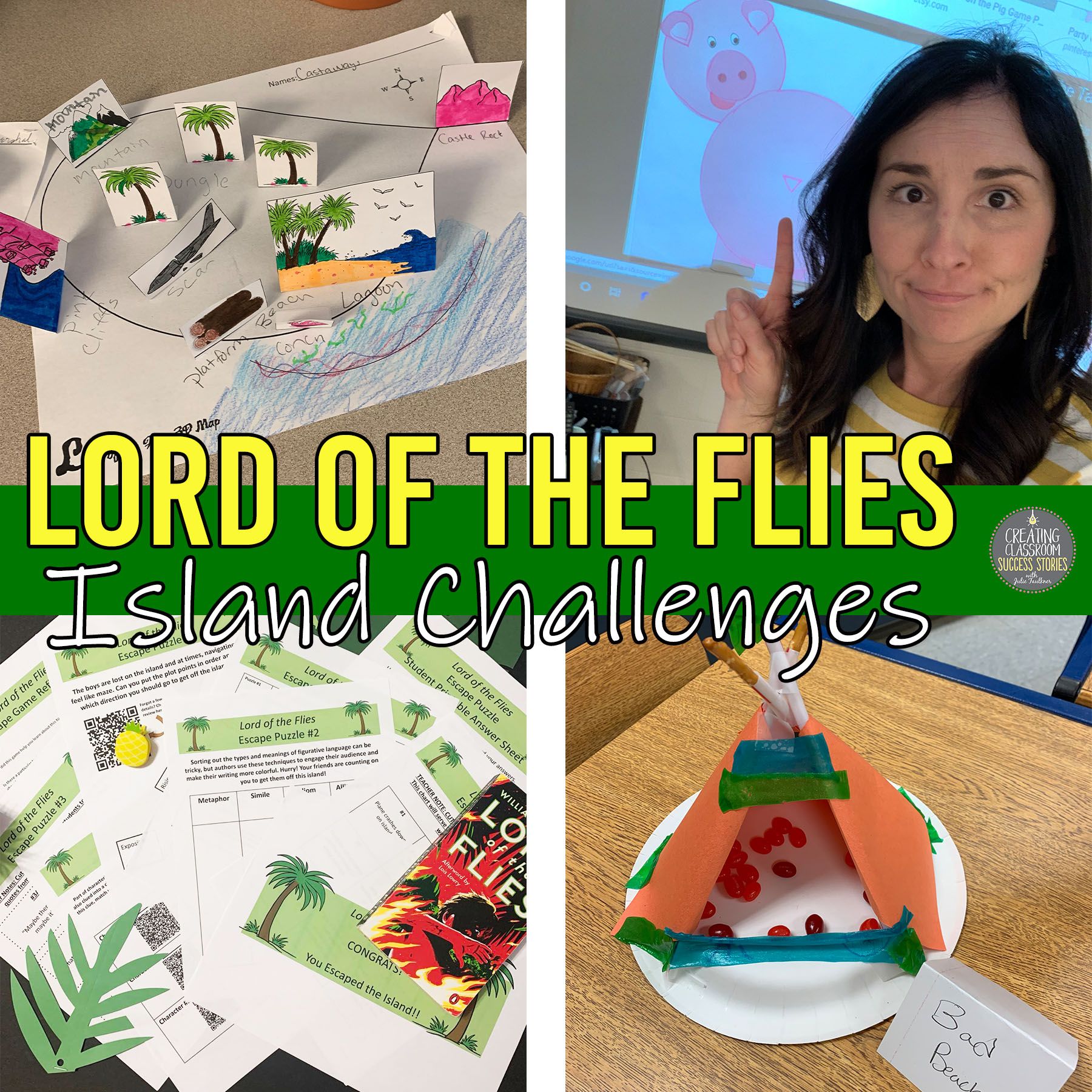

A strong novel study doesn’t begin on page one. Before students ever crack the spine, they need a sense of why this story matters and how it connects to the skills they’re expected to master. And they need excitement, interest, and intrigue! Students deserve the chance to experience a full narrative arc, and that starts with intentional framing.

At the beginning, consider:

- Introducing essential questions that will anchor the entire study

- Previewing themes, historical context, or author background

- Using short nonfiction, images, videos, or artifacts to spark curiosity

- Setting expectations for stamina, note-taking, and discussion norms

One of my favorite ways to get all of this done (without the boring slideshow) is with stations. Intro stations get students up and moving while signaling novelty to them in a way that creates organic interest and buy-in. Read more about how I start a novel study here and see how I conduct stations with large class sizes here on Teachers Pay Teachers or here on Instagram in my free teaching tips video series.

At the end, stick the landing by:

- Synthesizing themes and tracing how they evolved

- Revisiting essential questions with deeper insight

- Connecting the novel to contemporary issues or real-world implications

- Ending with a culminating writing task or seminar that proves mastery

Beginning and ending with intention ensures the novel study feels cohesive, rigorous, and meaningful — not just “we read a book.”

2) Build Reading Stamina Through Structured, Purposeful, Active Reading

One of the biggest pain points educators and parents are experiencing right now is why students struggle with long-form reading. College professors are reporting that students arrive unprepared for the reading load and are unable to engage with lengthy or complex texts. This is directly tied to the rise of excerpt-driven curricula.

Whole novels uniquely build stamina — the ability to hold onto ideas, track character development, and sustain attention across chapters. Excerpts simply cannot replicate that cognitive endurance or build authentic student engagement.

And I’ve seen this firsthand.

My niece is in middle school right now, and her class is “reading” a novel — except she couldn’t even remember the title of the book when I asked her what she was studying in her ELA class. She told me they listen to audio, answer (surface-level, I presume) questions, and move on. No active reading. No discussion. No ownership. No creativity. It’s the illusion of a novel study without any benefits. Saddest. Story. Ever.

Honestly, this is exactly why some curriculum coaches believe whole novels “don’t work.” They’ve only seen them taught this way.

To build true stamina, incorporate:

- A mix of independent reading, partner reading, and teacher modeling

- Interactive tools like Nearpod, symbol trackers, or emoji/character puppets with prompts/questions built in

- Quick writes or guided annotations of close readings that keep students mentally engaged

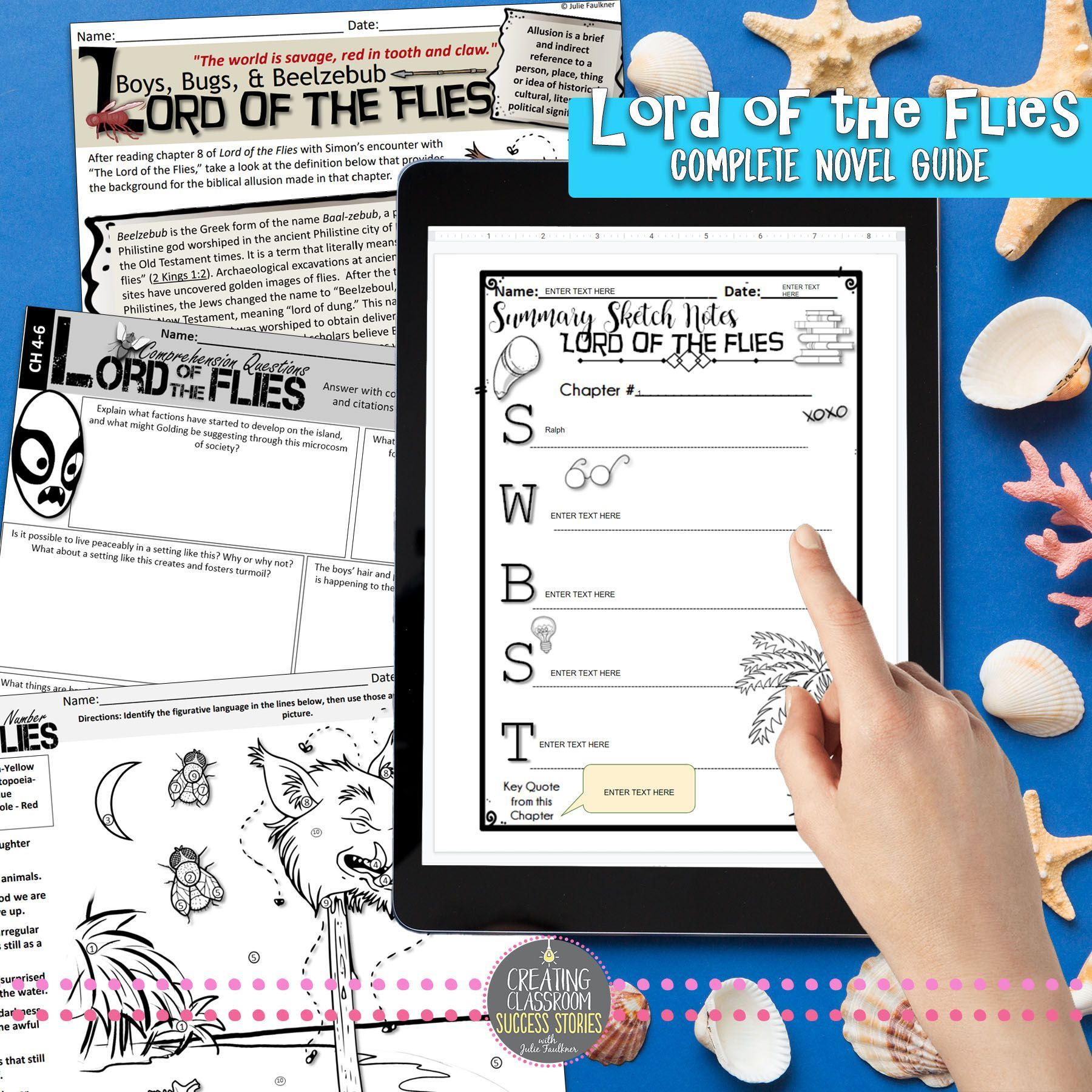

- Regular check-ins with summarizing sketch notes that require students to recall earlier chapters

- Text-based comprehension questions for use during reading that require careful reading and response (See how to make your own student workbooks for any novel study here on my IG)

As one literacy expert notes, students need exposure to whole books to learn how to “hold onto parts of the beginning of the story as the rest unfolds over time”. That’s stamina — and it’s essential for college readiness.

3) Flood the Study with Meaningful Writing Tasks and Paired Texts

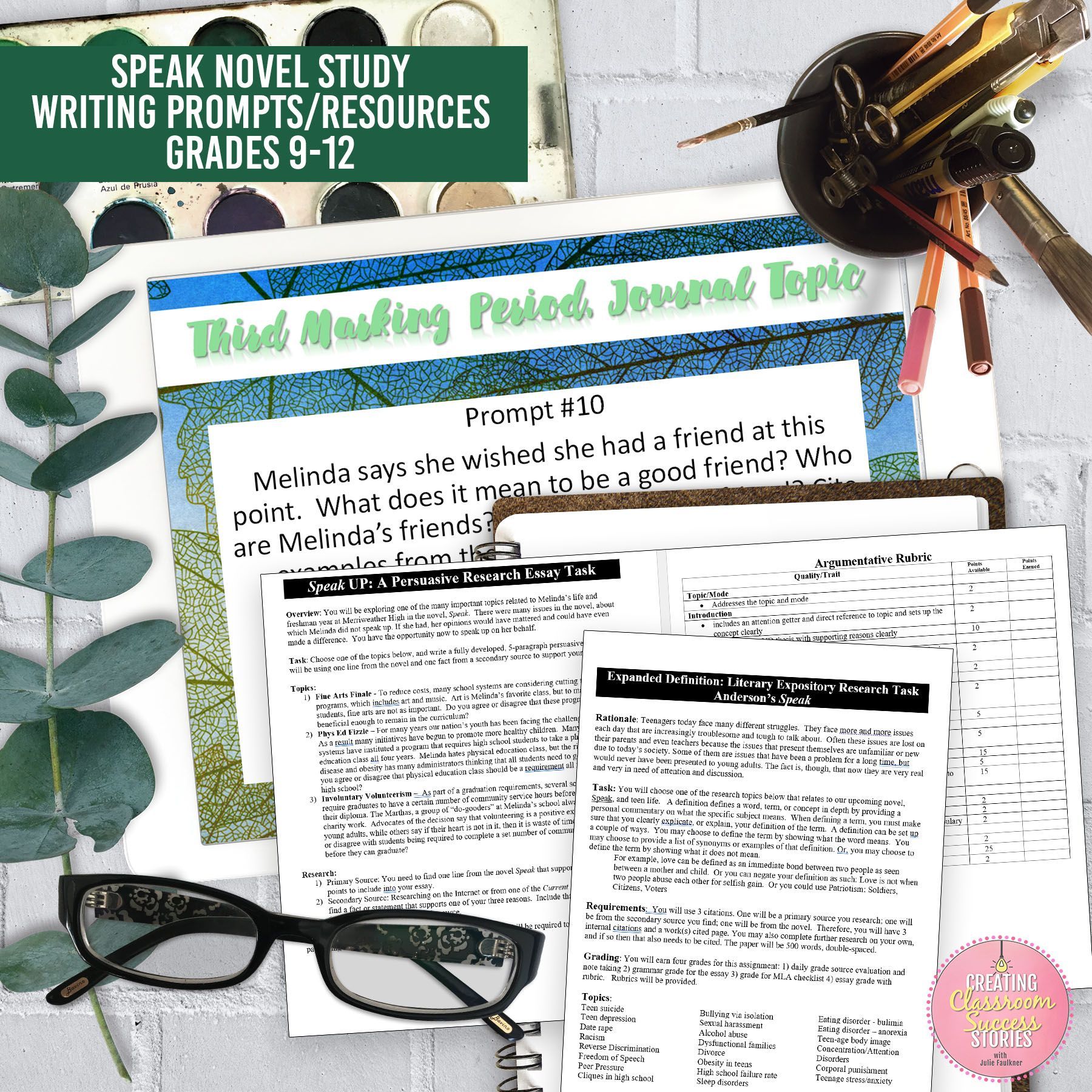

If you want your novel study to be truly standards‑based, writing can’t be an afterthought. And it can’t be the “How do you feel about this character?” kind of writing that fills time but doesn’t build skill. Students need writing tasks that require analysis, argument, synthesis, and evidence — the exact skills they’ll need in high school, AP courses, college, and beyond.

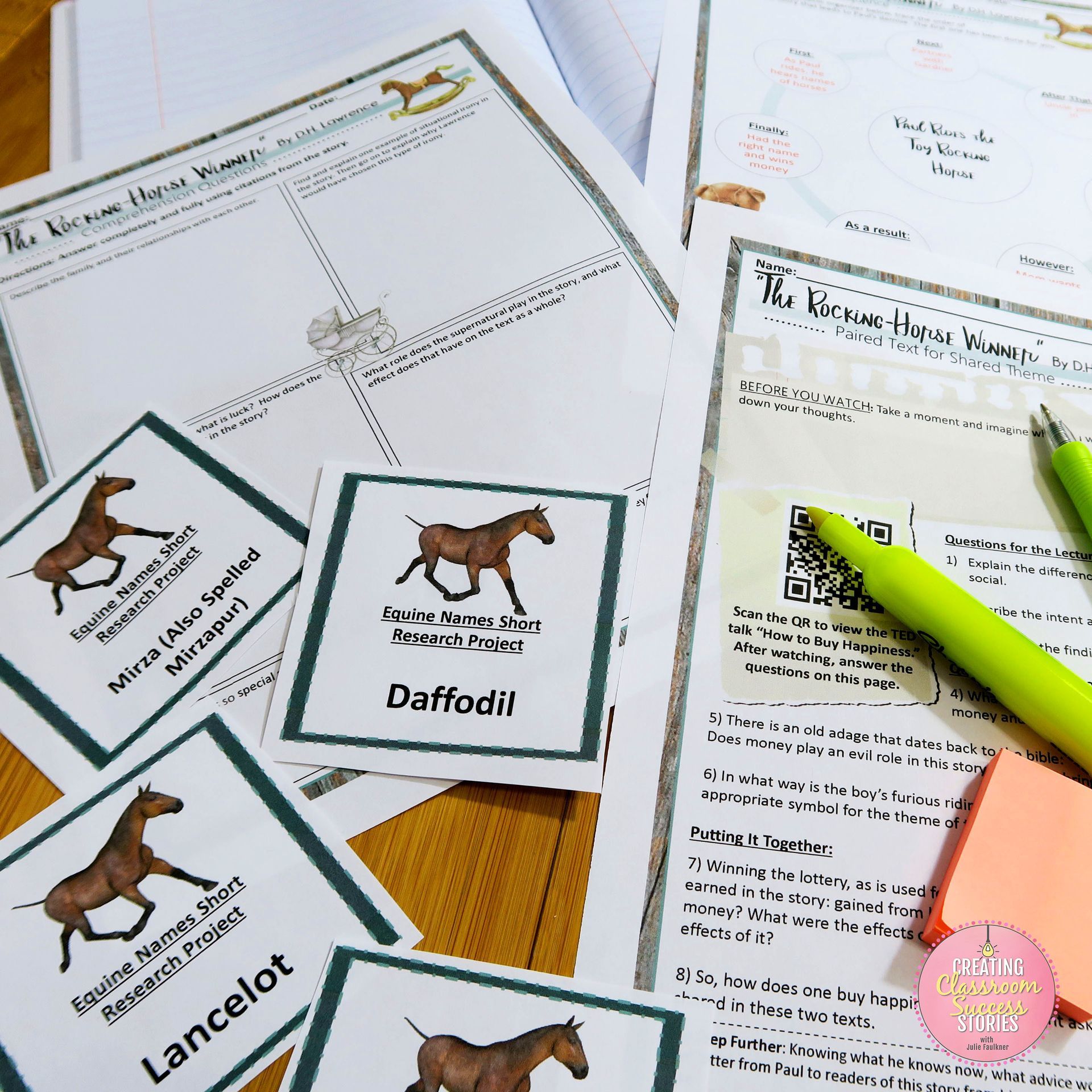

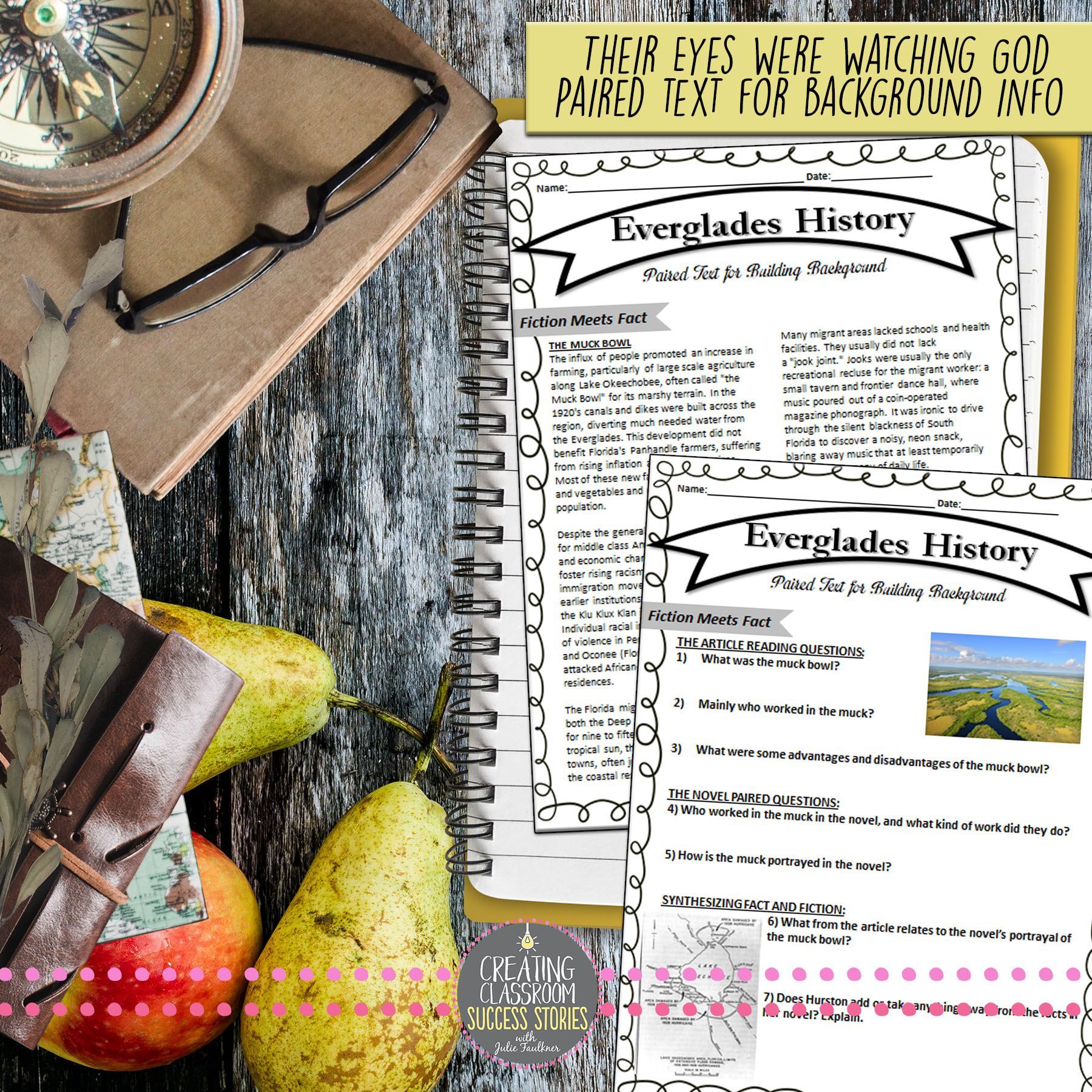

This is also where paired texts become your secret weapon.

Curriculum coaches often push excerpts because they believe short texts make it easier to “hit the standards.” But pairing a full novel with high‑quality nonfiction, articles, videos, primary sources, and short research tasks actually expands your standards coverage — and proves that whole novels are not only rigorous, but deeply aligned to ELA expectations.

Whole novels teach complexity:

- theme development across time

- structural choices

- character arcs

- author craft

- sustained argument and synthesis

Paired texts help students connect that complexity to the real world, to informational reading standards, and to writing tasks that matter.

Meaningful writing + paired text tasks might include:

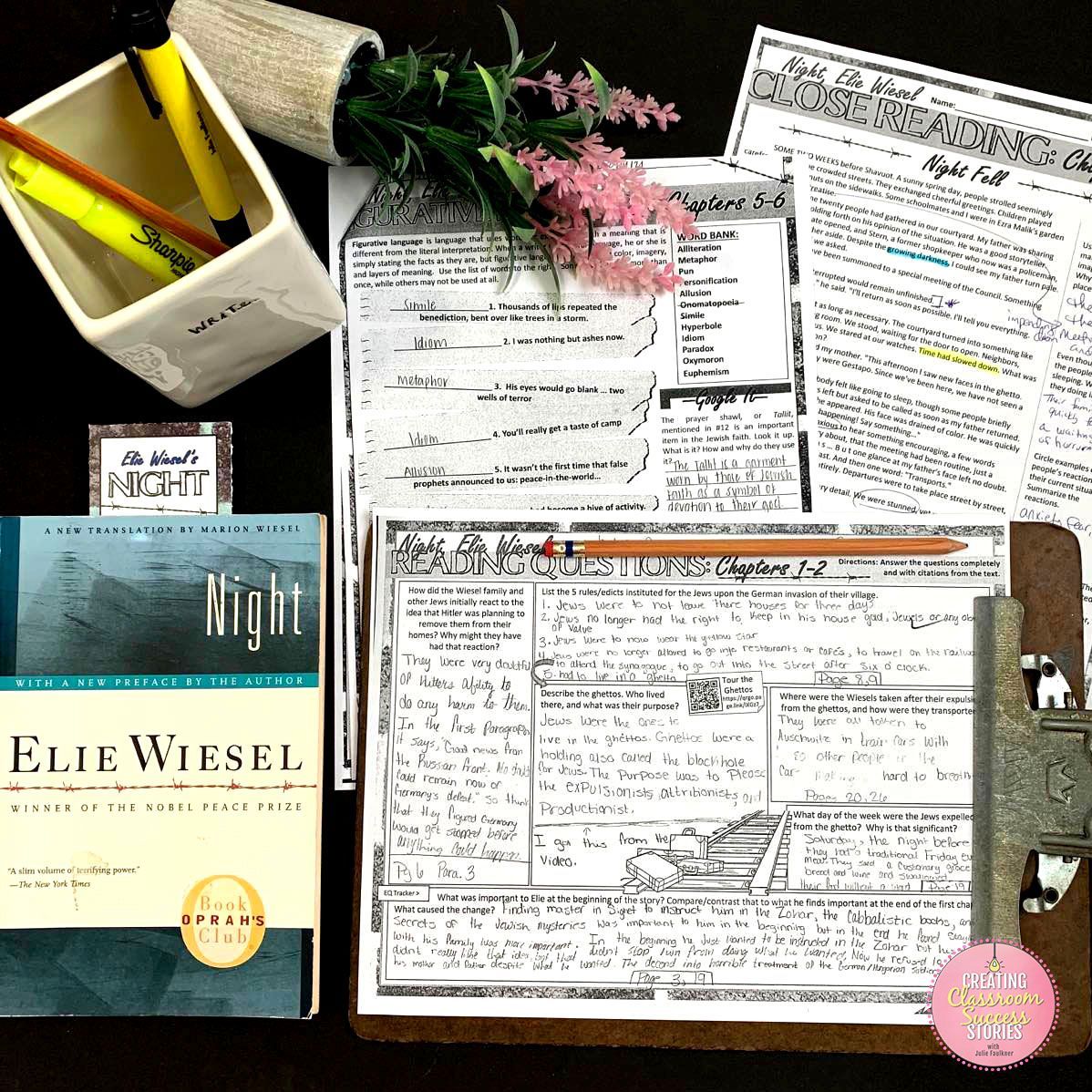

- Analytical paragraphs using text evidence from the novel

- Argument essays that connect the novel to nonfiction sources

- Short research projects that build background knowledge or explore themes

- Rhetorical analysis of the author’s craft, structure, or choices

- Synthesis writing that blends the novel with articles, speeches, or historical documents

- Creative responses grounded in the text and supported with evidence

This is also where Advanced Placement and college readiness are built. Students who only write from short passages struggle to sustain arguments across longer texts — a skill essential for AP Lang, dual enrollment, and college-level reading loads. Paired texts + whole novels give them the practice they need to think deeply, write clearly, and support claims with evidence from multiple sources.

When you combine meaningful writing with intentional pairing, you’re not just teaching a novel — you’re teaching students how to read, think, and write in a world that demands depth.

4) Make Discussion the Heart of the Novel Study

One of the most common searches right now among teachers them asking how to make novel studies more engaging and community-driven. The answer is simple: discussion.

Whole novels create a shared experience — a common text that students can wrestle with, question, debate, and interpret together. This is something excerpts cannot replicate. As one curriculum leader notes, the most valuable part of reading a novel as a class is “the common project of engaging other young people in a conversation about a book that is open to multiple interpretations.”

To make discussion central:

- Use book clubs or literature circles (see my post series on book clubs here)

- Host discussions at key turning points

- Provide structured, text-dependent questions with task cards

- Encourage students to bring their own evidence to the table

- Build routines that help quieter students participate meaningfully

Discussion deepens comprehension, builds community, and helps students internalize the novel’s ideas. It’s also one of the most joyful parts of teaching literature. Read

my post about effective classroom discussions here.

5) Keep Every Activity Text-Based — Even the Fun Ones

Novel studies should be fun — but they should also be rigorous. The key is to keep every activity anchored in the text. This is where you can push back against the misconception that whole novels lead to “fluffy projects.”

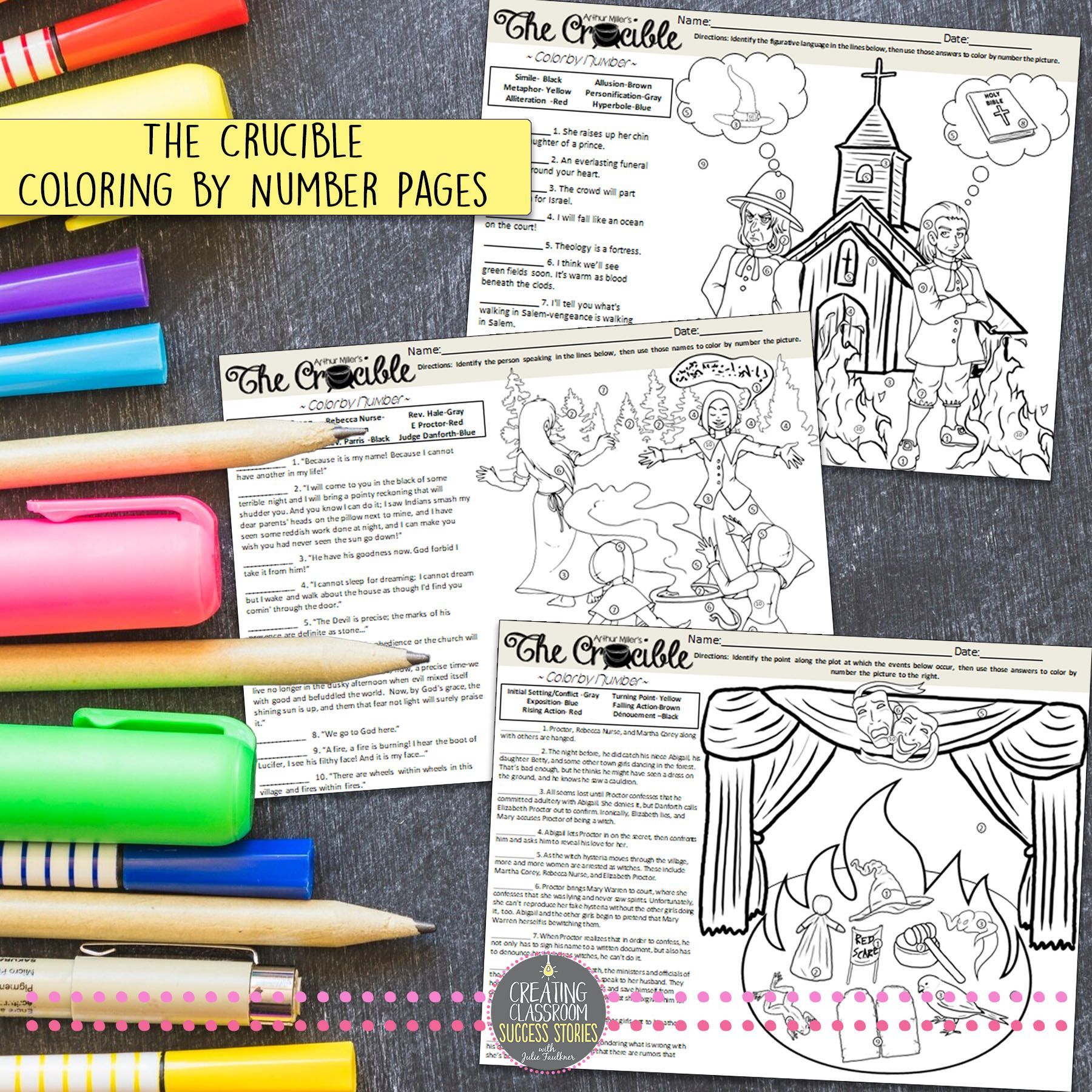

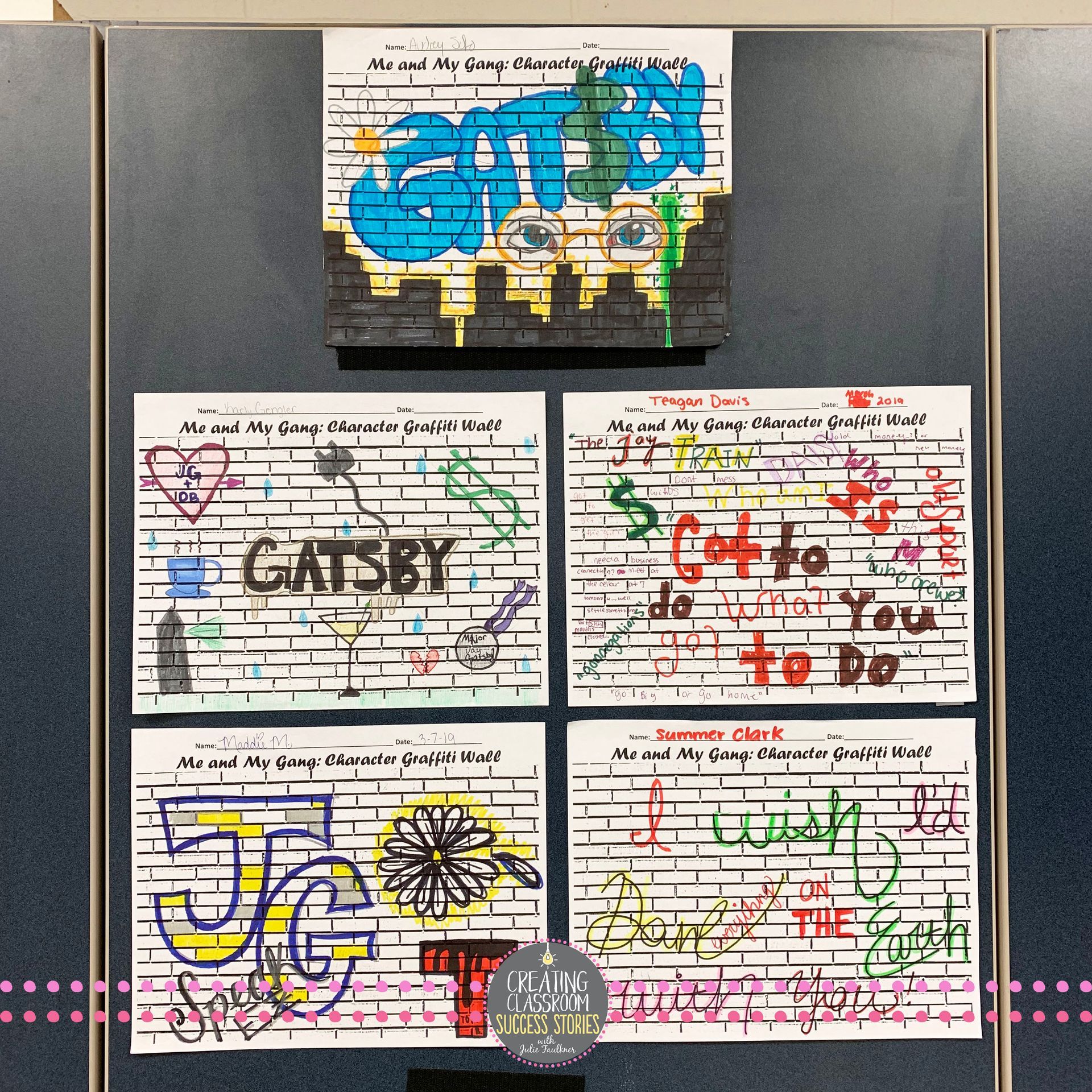

Text-based fun might include:

- Character TikToks supported by textual evidence

- Theme playlists with cited lyrics and passages

- Courtroom trials where students argue from the text

- Visual one-pagers that require quotes and analysis

- Creative writing that mirrors the author’s style or structure

The rule is simple: If it’s not grounded in the text, it doesn’t belong in a standards-based novel study.

This approach maintains high rigor while still honoring creativity and student voice. Read more about curing “activity-itis” in this blog post.

Conclusion: Why Whole Novels Still Matter

Some argue that excerpts can teach the same standards as a full novel. And while that’s technically true, it’s incomplete. Excerpts can teach skills; novels teach endurance, synthesis, and the ability to follow extended arguments — the very skills college professors say students are lacking. Standards are the floor, not the ceiling.

Students deserve (and actually want) more than snippets. They deserve stories they can live inside, characters they can grow with, and ideas they can wrestle with over time.

Whole novels still matter.

And when taught with intention, alignment, and depth, they prepare students not just for tests — but for the real reading demands of college, careers, and life.